Jaw trauma is common in dogs and cats. Fractures to the jaws comprise 6% of all skeletal trauma surgery. New dental techniques, combined with standard surgical techniques, are often available to provide fracture repair without the need for invasive surgery.

Advances in jaw fracture fixation have led to much better success rates. We attended the first ever AOVET North America course in Las Vegas in February 2013 on the Operative Treatment of Veterinary Craniomaxillofacial Trauma and Reconstruction to keep fully up to date in this exciting area.

With any jaw fracture it is absolutely essential to support the fracture site early in the case with a tape muzzle or soft Mikki muzzle as soon as practically possible - see image below. Tape muzzles are simple and inexpensive. A useful tip is to use a syringe case or barrel between the incisors to ensure there is enough space for the tongue to lap water and liquid foods. Most surgical texts show this - Fossum's Small Animal Surgery page 902/903 and Verstraete & Lommer's Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery page 276.

- Use 1 or 2 inch wide tape depending on size of dog. Place a strip adhesive side out round the muzzle to create a loop.

- Remove the lop and place a second loop adhesive side down over the first loop. Neither loop now has a sticky surface exposed.

- Replace the loop back on the muzzle and draw marks where the behind the ear ties will go so that they do not make contact with the eyes.

- Remove muzzle. Premeasure four 18" strips of 1" tape. Place one strip along muzzle, adhesive side out, on pre-marked location of first loop with an overlap and fold over. Place second 18" strip over first 18" strip adhesive to adhesive. Repeat on other side.

- Replace on patient. Tie behind ears and assess occlusion. If too big or small the muzzle can easily be cut and bridged with additional tape to make bigger or smaller.

We frequently see cases where support has not been provided. As a result the weight of the fractured jaw pulls on the tissues and blood vessels making subsequent healing difficult if not impossible. Surgery is best performed as soon as possible once life threatening injuries are stable. Normal orthopaedic techniques are tolerated very poorly by the jaws. There are a number of reasons for this.

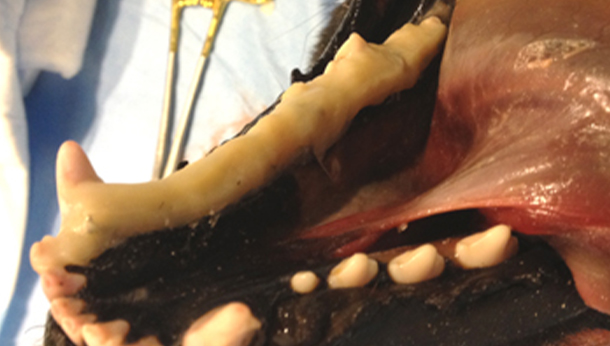

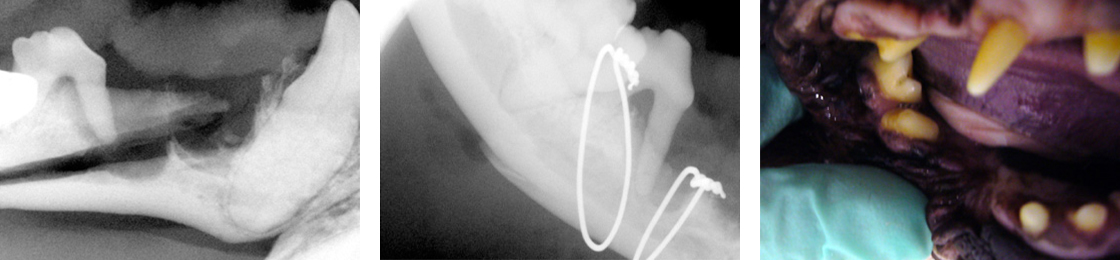

Firstly, poorly placed pins or plates are likely to damage the tooth roots or neurovascular structures and contribute to further pain and instability. There is very little space to place a pins or a screw in either upper or lower jaws. The images below show the use of miniplates on head trauma. The limitations to screw placement is clear.

Secondly, it is very important to provide normal dental occlusion in order to allow the mouth to shut and return to normal function. Fracture alignment is important but secondary to good occlusion of teeth.

Thirdly, these problems are often seen in animals that already have significant dental disease and/or poor bone quality and volume.

Inter-dental wiring combined with composite resin splints on the teeth can be used to treat extensive fractures. A number of techniques are described in the surgical textbooks. The Ivy or Stout Multiple Loop Techniques work very well and are easy to master as long as there are sufficient teeth to act as anchors.

Inter-fragmentary or cerclage wires are also often used. Titanium miniplates and screws are excellent in circumstances where they can be placed safely.

If a splint is placed it is essential that the teeth on the opposite jaw do not make contact with it - otherwise it will be destabilised. The splint on the mandible below can be placed on both buccal and lingual sides as far caudal as the fist molar (carnassial). From this point it can only be placed lingual otherwise the maxillary teeth will make contact as the mouth closes.

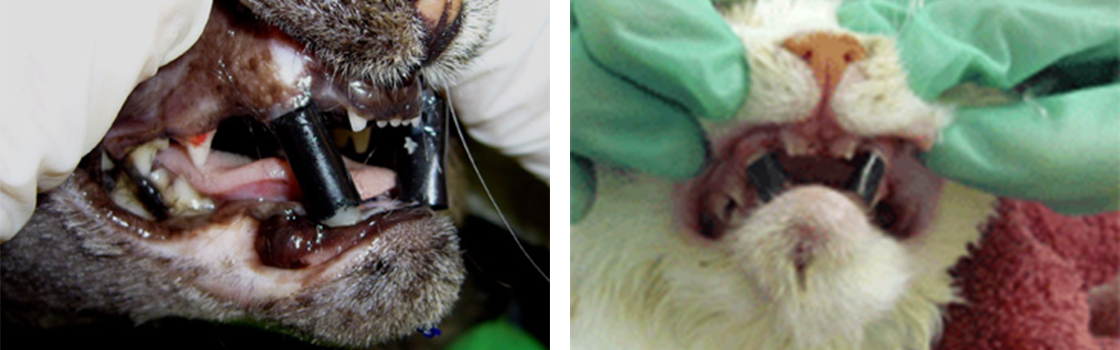

Additionally, cats and small dogs less than 10kg lend themselves well to the bonding together of upper and lower canines - maxillary/mandibular fixation or MMF. This can provide a stable environment for healing with the cat or dog still being able to lap soft foods through the gap. It is very important not to have too wide a gap between the upper and lower incisors as swallowing is then impossible. A gap of between 5mm and 10mm between the incisor cusps is considered optimal. Feeding tubes (oesophageal) may be placed for initial nutritional support but can often be removed in 2 - 3 days.

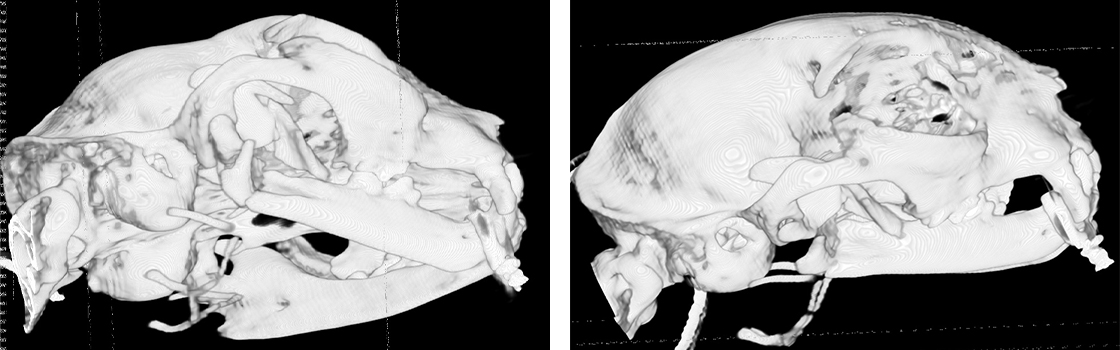

The CT scans below show a comminuted fracture of the right caudal mandible body very close to the TMJ. Radiographs did not fully show this damage. This cat also had a cerclage wire placed round the symphysis in addition to MMF.

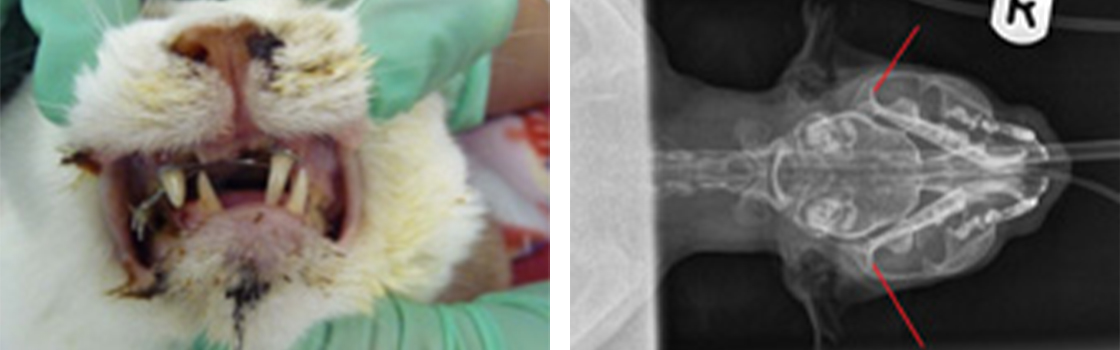

The case series shown below shows a different cat that presented with multiple head trauma. The referring practice had attempted to stabilise the jaws with wires. The effect of the wires being too tight was to destabilise the fractures further and leave sharp wires in the mouth damaging the soft tissues extensively.

The radiograph shows that, apart from the symphysis separation, there is no other significant fracture. Note, however, the deviation and shortening of the mandibles. This is common in cats once the powerful masticatory muscles re-align themselves following symphysis separation. The red arrows show the condylar processes on the mandibles. Note the symmetry proving no TMJ luxation.

The jaws very often re-align under GA without difficulty. They just won't stay there! Our solution is to place a bonding agent between the upper and lower canine teeth using a cut-down drinking straw as a retainer. If there is a cerclage wire round the symphysis the cut end below the chin can be grasped with forceps to guide the jaws and hold them there while the material sets.

If the jaws stay aligned for 2 - 4 weeks the material can be removed. The result with Phoebe was excellent.

One word of advice when selecting wire for interdental wiring techniques or cerclage wires in feline symphysis separation. Many texts and journal articles advise the use of 20 SWG wire for cats. This is far too big and hard to use - 24 SWG is far easier to use and plenty strong enough. Also, never leave the cut ends in the mouth or exposed under the chin see the image above in the first of the case series. Cats love to rub their chins and a jagged end of a wire will cause unnecessary trauma to soft issues.

We prefer mandibular cerclage with the wire ends both ventrally via a stab incision in the skin - see here for technique courtesy of Veterinary Dental Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner (Holmstrom, Frost & Eisner). An alternative technique is described in Verstraete & Lommer (page 267).

The radiograph below shows an ellipse round a caudal mandible fracture in Harry The Cat. Inter-canine bonding worked very well in this case with full healing in 4 weeks.

Many dogs with periodontal disease of the teeth suffer from pathological fractures of the mandible from minimal trauma. Lack of teeth can be a challenge but occlusion as a primary objective, with rapid return to function as a close secondary objective is still necessary. Flo (French Bulldog) was kicked by a horse and fractured her right mandible. The site was open and infected. This healed well with twin cerclage wires once the compromised teeth and infected tissue was removed. The radiographs below show her before and after surgery and the photograph is of her right mandible 6 weeks following wiring.

TMJ conditions are also common in trauma cases – particularly in high rise syndrome in cats. Luxation of the condyle is easily resolved but fractures of the condyle or zygomatic process of the temporal bone can be challenging to diagnose and resolve. CT scanning provides excellent imaging in these cases.

Remember - the mouth must be able to shut after surgery.